L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

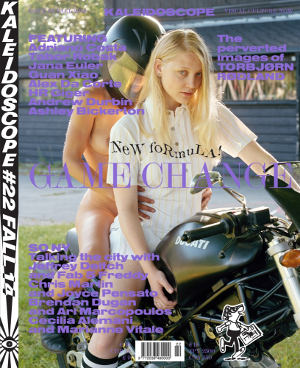

Kaleidoscope Anno 5 Numero 22 autunno -inverno 2014

Torbjørn Rødland

Hanne Mugaas

Interview

a contemporary magazine

HIGHLIGHTS

BOYCHILD by Francesca Gavin

ED FORNIELES by George Vasey

ADRIANO COSTA by Laura McLean-Ferris

LIU CHUANG by Venus Lau

CAROL RAMA by Jesi Khadivi

TABOR ROBAK by Alex Gartenfeld

JANA EULER by Martha Kirszenbaum

GUAN XIAO by Pablo Larios

ALEX DA CORTE by Piper Marshall

DAVID OSTROWSKI by Peter J. Amdam

APHEX TWIN by Francesco Tenaglia

TOREY THORNTON by Ross Simonini

MAIN THEME – SO NY!

JEFFREY DEITCH and FAB 5 FREDDY

CHRIS MARTIN and JOYCE PENSATO

BRENDAN DUGAN and ARI MARCOPOULOS

CECILIA ALEMANI and MARIANNE VITALE

MONO – TORBJØRN RØDLAND

Essay by Chris Sharp

Interview by Hanne Mugaas

Portraits by Trine Hisdal

VISIONS

“Chopped & Screwed: AUSTIN LEE and DAVID BENJAMIN SHERRY,” curated by Alessio Ascari

“Biomechanoid” by H.R. GIGER

“Paintings” by DOROTHEA TANNING

“From A to B via C” by ALEXANDRA BACHZETSIS

“Rondes Bosses” curated by Nicolas Trembley

“Technical Compositions” by CHRIS WILEY

“$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$” by DAVID RAPPENEAU

REGULARS

FUTURA 89+: Andrew Durbin interviewed by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Simon Castets

PRODUCERS: Carter Cleveland interviewed by Carson Chan

PANORAMA: Francesco Clemente’s India by Christopher Schreck

PIONEERS: Ashley Bickerton interviewed by Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen

John Armleder

Andrea Bellini

n. 21 estate 2014

Voiceover: Under the skin

Shama Khanna

n. 20 inverno 2013-2014

Yang Fudong

Davide Quadrio e Noah Cowan

n. 19 autunno 2013

Massimiliano Gioni

Francesco Manacorda

n. 18 estate 2013

John Currin

Catherine Wood

n. 17 inverno 2012-2013

Prisoner of Flesh

Michele D'Aurizio

n. 16 autunno 2012

The works in your book I Want to Live Innocent (2008), which were all shot in Stavanger, really succeed in capturing the different layers of the place. How did the city shape your vision as an artist, if at all?

Like Stavanger, I was internationally oriented from the beginning, while still trying to filter the interpersonal aesthetics of a world-centric culture through personal and more spiritual concerns. I honestly don’t know how much of that should be traced back to my hometown, but there is an argument that could be made if you really want to.

You did start your creative work in Stavanger though, and you’ve been very involved with its music scene; you’ve designed the record covers for Noxagt, and the visuals for the band you were in, Bever.

Oh, I never played with them. Where did you hear that? I played the oboe as a young teen but never in a band, always solo. That is the story of my life. I made small drawings, posters, band photographs and record covers for Bever—and saw a lot of their concerts.

This reminds me of the Jeremy Deller’s The Search for Bez (1994), where he goes to Manchester to try to locate Bez, the Happy Monday’s famous non-member. What kind of music did Bever play? What kind of music were you listening to back then as teenager in Stavanger when the band was active?

Bever was like Primus but with a message. Norwegians hadn’t really opened up to black music in 1991, so I fed the bass player homemade mix tapes filled with Bootsy Collins, Sly Stone, Rick James, Roger Troutman and The Meters, encouraging him to keep Bever funky. I was twenty-one. At fourteen I had discovered Bruce Springsteen and David Bowie; at fifteen Tom Waits and Prince; at sixteen Marvin Gaye and The Smiths; at seventeen Joni Mitchell, Public Enemy and John Coltrane. And then it went downhill from there.

Is music still an important part of your daily life? What do you listen to now?

It still is a daily drug. To find truly challenging music is of course increasingly difficult. I’ve learned to appreciate a lot of different artists and genres. Lately, I’ve been into original Broadway cast recordings of Sondheim musicals. On one level they’re really really good but they can also be disagreeable, quaint and hard to love. Sunday in the Park with George (1984) is pretty incredible.

I’m curious about the picture of the hip-hop stars. Where was it taken?

You mean the hip-hop poster photographed with three types of red jam on it? I think I bought that poster in Switzerland. It’s a reproduction of a fan drawing, a messed up group portrait in pencil. Those MCs are of my generation, I think I can say that, and I made the photograph with my largest camera in a rented house in Stavanger. The title is The Power of Goals (2006). I was interested in the relationship between American self-help books and mystical traditions. Rhonda Byrne’s book The Secret was topping the bestseller lists at the time.

Twelve years earlier I had been very impressed with Biggie Small’s first album, Ready to Die. And then, after his second album Life After Death, he was killed. Tupac Shakur has even more lines or lyrics about being shot and dying. But also the gangster rappers that survived the nineties seemed to rely on The Secret—or Fake It Till You Make It. These talented black teenagers were sitting in their mother’s houses making up confessional lyrics about an excessive sexist-materialist lifestyle that they could try to make a reality after perhaps two big albums.

Are you still interested in the model of hip-hop? Now, I think it is best encapsulated by Jay Z’s famous line, “I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man!” For example, Dr. Dre has an office at Apple these days.

I’m not particularly fascinated by branding and empire building. I’m talking about the strong influence of fiction on reality. I’m very interested in unconscious life strategies and how they’re linked to personality types described in the enneagram. Enneatype threes, like Jay Z, can be great team builders but as a rule they’re not the most interesting artists. Threes lie too easily.

Recently, while going through the archive at Kunsthall Stavanger, I found a clipping with a newspaper drawing of yours, from 1990. Turns out that instead of delivering newspapers as a teenager, you actually drew satire for the local paper. How did you get the job? Was this the first public outlet for your creative work?

Yeah, but was I an artist back then? I don’t think so. Those drawings served a function in the paper and it gave me a rush to push myself to finish them just hours before the newspaper landed on people’s doorsteps, but they were never very good. I was sixteen or seventeen when I contacted the editor. I knew he had just lost his caricaturist to another local newspaper that was just starting up. I was always a confusing mix of very shy and very confident. Doing that work was a real education. I slowly realized that I was interested in visual symbols too subtle for mainstream media. This pushed me towards the art world and to photography.

Is your Andy Capp series related to your newspaper drawings?

It must be. I spent my whole childhood drawing cartoonish men. The “Andy Capp Variations” (2009) show my need to integrate direct observations of the everyday with a flat and dead, yet culturally recognizable cartoon character.

Your work is said to be uncanny, but I also think there’s a lot of humor to it. What role does humor play in your work?

It’s a part of life. It’s in the pool from which I pull my material. But the movement is never towards humor, towards comedy. Non-Progress, the film work from 2006 that is included in our Stavanger exhibition, is in retrospect an almost pedagogical example of this: We see some of Mitch Hedberg’s jokes performed in front of us, but they’ve lost most of their humor. The movement is away from funny and towards an underlying complex coherence. That’s at least how I see it. What does a joke contain when it’s no longer funny?

Do you see or listen to comedy?

I subscribe to some comedy podcasts. And I’m not alone. I think a lot of young artists have an interest in stand-up and comedy. There is a one-sided identification. Both artists and comedians are cutting and licking the edges of what contemporary culture can accept as a mirror image of itself. Since moving to Los Angeles four years ago I’ve been invited (by other visual artists) to see more comedy shows than theater, or even concerts. Cinema is still number one, though.

You recently joined Instagram with the account @theyellowshell, where you posted a picture of you with Paris Hilton. Did you work together?

I said yes to session with her for Purple Magazine simply because she was already on an imaginary list of people I’d want to work with. Celebrity is more interesting when it’s pure and self-contained; when it doesn’t disrupt an artistic project; when the image is its own content.

How was it meeting her? I (kind of) hate to be so gossipy, but it’s very interesting.

Well, I had no chance of communicating with her in advance. Hollywood publicists don’t exactly make things run smoothly. They wouldn’t send her my questions before I provided a mood board, and I was of course not going to fake a mood board. So when I showed up at her house I didn’t know which pets were available or what ideas she would be open to, and she had no idea why the magazine didn’t send a fun celebrity photographer like Terry Richardson. To make a long story short: she was uncomfortable because she was not in control. I can understand that. I didn’t allow her regular squad to do her hair and face, I didn’t play loud dance music, the clothes we brought were relatively unsexy, my cameras were analogue and old-looking and the ideas weird.

What’s your relationship to fashion and contemporary photography? Do you take on jobs in fashion (like with Paris Hilton), and where do you place this work?

If you’re a good poet, people don’t assume you’re in the business of advertising luxury items. I understand that, historically speaking, art and commercial photography are linked, but you’d think that after postmodernity there’d be a place for photographers to work with the complexity of their times and their medium, like painters and rappers do, without being pushed towards indirect advertising. I haven’t done advertising. I sometimes say yes to collaborate with magazines and it’s always complicated. The Purple collaboration with Paris Hilton is about access. I wanted the portraits for myself. They would never have happened without the magazine. Recently I’ve also collaborated with Double and Wallpaper. There’s a stylist involved, but I choose everything I photograph. I’m afraid the distinction between asking for a pair of red pumps and being presented with and asked to do something with a pair of red pumps is lost in the magazine context. For me it’s an important one. So I’m more comfortable later on when I can include the picture in my own publication or exhibition.

Is there a photograph you took, when you—the photographer— were not in control? Is this of any interest to you?

Oh, definitely! With photography control is always partial. Making analogue double exposures is about giving up even more control. I would not be interested in building a layered photograph like that in Photoshop with actual control. I improvise a lot, but first I need to set up or plan a platform interesting or strong enough to improvise from.

I think of LA as the perfect place for you.

Why is that?

It is a town that revolves around “the industry,” and I picture you as a kind of photographer who likes to work silently on the fringes. While everyone is looking towards the moving image, and even comedy— which is a feeder system to the moving image—I imagine it gives you time and space to look the other way. Also, of course, the weather. After growing up in Stavanger, where it rains basically all day, it can’t hurt. Why do you like it there?

It’s true that I am a little turned off by this feeling you get in New York of fine art as the big tent; the main activity. In Los Angeles artists are still outsiders stumbling out of the numerous art schools and quiet hideaways. I grew up where the city of Stavanger ends and the farmland takes over. The Hollywood hills offer a not entirely unfamiliar mix of countryside and city living. There’s a strong sense of privacy. There’s room for an unproductive idea.

How long does it take from the initial idea to when the photo is taken?

It varies. Typically somewhere between ten minutes and … ten years! I carry around a number of dumb visual approximations, often passively waiting to meet people who’ll help me externalize them.

Do we have to say “photo”? To me that’s only slightly better than calling them “captures.” I also don’t identify with pictures being “shot” or “taken” because that is not what it feels like at all, at least not when you’re on a tripod, and I’m still chained to the tripod. In the same way that an Inuit can decide whether or not the word Eskimo is derogatory, I should have a say in this, don’t you think? Words do carry ideology.

Are the images you post on Instagram photographs?

That is a very good comeback. Some of them are definitely photographic snapshots. But Instagram is tertiary.

I’ve noticed that you always carry a portable camera, photographing people you meet—also without their consent. Is this research? Do these situations ever become uncomfortable? The camera obviously changes the social setting.

It’s not research! It’s a very different way of producing images. In thirty years they’ll be interesting. You’re right: doing them does feel a little aggressive at times, which my work with bigger cameras never does. I don’t like looking at people through a camera that I hold in front of my face. That relation is too asymmetrical. I put the camera away when the situation gets uncomfortable. I hope I do. But sometimes you just have to do your job.

Do you have a compulsion to always photograph / record?

Hmm, there is a drive to make and a joy of collecting images. It’s a good thing. I’ve seen it die in photographers who embrace the world of commercial photography.

Many people do videos now, where they once took still images. Does the shift from still images to moving images—which can be seen on sites like Instagram and Vine—interest you at all? What’s your experience with video, how is it different and how does it change your work?

I made my first video, The Exorcism of Mother Teresa, early in 2004—before YouTube happened and before telephones or regular SLRs could record moving images. It was more inspired by cheap anime and by those non-narrative and largely silent programs produced to show off new television sets. The films contain more indicators of how they should be seen. My photographs give weaker clues about the worldview that produced them. For one thing, it was satisfying to work so directly with music. With the exception of the one we’re showing in Stavanger, all six films have an original score.

Are you a gear head? I know some photographers can talk forever about formats, cameras and lenses while others don’t pay much attention. Photography is a technology- intensive practice, so I am curious to hear what your angle on it is.

After all my stuff was stolen from the small van that moved me from Berlin to Oslo in late 2002, I went out and bought the exact same cameras and lights that I had lost. I still use them today. So no, I’m not particularly focused on new tools. A new lens is dramatic.

Do you plan everything in advance? How about the people populating your work—do you seek out specific types (professional models?), or do you get ideas when you meet people?

In 1997, when I first worked with models—after having been my own model for years—I did plan everything in advance, but I soon developed a more organic approach. I learned to trust the situations I create and let them live a little. I typically know what direction the setup should be pushed in, but I don’t necessarily know how far to push or exactly what this push ought to look or feel like. I’m open to alternative forms. Casting is crucial. I’m photographing or getting help from more artists now than I did ten years ago.

Several of the people you’ve photographed are semi-famous in different places. For instance, for your book, I Want to Live Innocent (2008), you’ve included people who are famous in Stavanger, but that wouldn’t be recognized in other locations. What do these personalities bring to your work?

The partial recognition complicates the reading. I always try to open up to layers of meaning that are outside of the here-and-now. Close to my portrait of someone you recognize in Innocent, you may see another picture of the same girl modeling wedding dresses in a taped up catalogue tear-out. I’m interested in these different layers of mediation.

Do the models themselves participate by changing the situation or the narrative?

Always. I seldom know exactly what will work. I think this is pretty common for intuitive artists: you don’t know what you want until it presents itself. What you end up doing should be richer than what you set out to do. With photography it’s amazing what can line itself up when you’re patient and ready for it. I always expect miracles. Didn’t we just talk about the power of goals?

How did you use yourself as a model?

My very first project was titled In a Norwegian Landscape (1993–1995). I worked on it as a student. I assumed I would stay with that project and that title forever, like Cindy Sherman and her “Untitled Film Stills.” I photographed myself as an urban wanderer in the forest. With my back to the camera I focused on the problems of having a nature experience and making art about it after the postmodern revolution had, for good reason, rejected the contemplative as a method of understanding oneself and one’s place in the world. In Scandinavia this series was embraced as a step into a postmodern mode of image production. My intention was for it to represent a step out.