Yasmina Reggad and

Bérénice Saliou are two young curators who work between Europe and North Africa.

In the last few years, they have both initiated residency programs for the mobility of artists in the Mediterranean area. We met during the opening days of the Venice Biennale and tried to get their point of view on the 55th International Art Exhibition. Not only we were interested in their opinion as – given their age and geographical location – they are incurring the risk of finding themselves in the middle of a huge socio-political change which will involve us as well, but also because their curatorial work highlights the production processes, rather than the exhibitory ones.

From our perspective, with this interview there emerge both the impulses and the contradictions of those who, like Yasmina and Bérénice, work in the so-called emerging markets: between the will of being recognized on a global level and the urge of giving an answer to the characteristics of the territory.

At the same time, it is evident how their answers indicate the possibility of telling and living the geography of contemporary art in many different ways.

First of all, can you tell us about the type of work you are carrying on with Aria and Trankat?

Bérénice Saliou: Trankat was conceived in 2008 by Moroccan artist Younès Rahmoun and myself and the non-profit organization Feddan was officially created in 2011 for implementing it. Back in 2008, there were a limited number of active structures in the contemporary art domain in Morocco. Almost all of them were in Rabat, Casablanca and Marrakech ; almost none of them was structured as a non-profit organization. The creation of Trankat stems from the lack of active, professional and internationally connected structures in the kingdom, and especially in Northern Morocco.

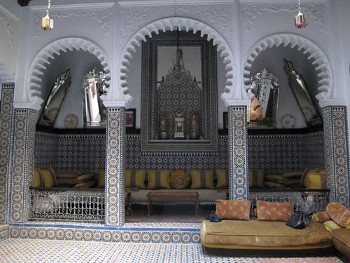

In fact, Northern Morocco and especially the RIF region, has been historically neglected. The two/three cities attracting tourists were Tangier, Chefchaouen and eventually Asilah. To a certain extent, this is still the case today, even though things are slowly starting to change. Trankat has been specifically conceived for the medina of Tetouan. This artistic residency, exhibition space and education program are located in a magnificent historical house of the medina (listed as Unesco’s world heritage), responding to the characteristic of the city and its unique academic situation.

Trankat invites international artists in residence to live at the core of the medina of Tetouan, work in connection with local artisans and give talks and workshops for the students of the three superior art schools of the city. The project also includes the organization of exhibitions and events.

Focusing on regional practices, these events explore the potential of such a richly ornamented environment at the antipodes of the white cube, while drawing attention on the medina of Tetouan and its hidden architectural treasures. Through intermingling contemporary art and traditional arts and crafts and shedding light on the medina at the same time, Trankat aims to promote artistic and cultural heritage while developing contemporary art and artistic education in Northern Morocco.

Which is your direction? And how -if doing so- are you looking at Europe?

Bérénice Saliou: We look at Europe as a partner and this collaborative dimension lies at the core of our project. In fact, Trankat is co-produced by the Moroccan organization Feddan and the French organization Sextant and plus, is based in Marseilles. This partnership for ¾ allows us to cross our networks and our skills, for other ¾ is also a way to increase our funding possibilities.

Furthermore, the decision of inviting international acknowledged European artists such as Jordi Colomer (currently A.I.R for three months) is a way to contribute to the development of contemporary art in Northern Morocco. We consider inviting established artists to produce works in Tetouan is a genuine way to support local emerging artists and the professionalization of the sector.

Not only our residents are encouraged to engage closely with the local students through workshops and talks, as once back at home they are our best advocates. They communicate with their peers about the extraordinary resources of Morocco and what is going in on there.

From your point of view, does the Biennale still represent a model for the artistic and cultural production?

Bérénice Saliou: I find difficult to address the Biennale as a definite, stable format. Nowadays, everything can be called a biennale as long as it involves artists and takes place every two years.

What is the link between the Venice Biennale, the Marrakech Biennale, the Young Creator of Europe and Mediterranean Biennale, and -let’s say- the International Biennale of Contemporary Art in Melle? By the way, have you ever heard of this Biennale in Melle? It is located in a very remote area in the countryside of France and its specificity is to feature artistic projects in relation with nature and landscape.

I think the Biennale cannot be taken as a model any longer because the term encompasses too many different realities. Every Biennale has its own requirements, its own goals to achieve. The Dakar Biennale 2013, for instance, only showcases artworks by African artists or artists from the African Diaspora. To be selected, works must be less than two years old, never sold or shown in an international exhibition.

In my opinion, biennales are platforms for promotion and visibility rather than models for artistic production. Although they surely generate the production of new works (by the invited artists), they rarely commission and produce them.

In which sectors do you believe the Biennale should be investing more? Could you present some best-practice models in this sense?

Bérénice Saliou: Again, the question is quite tricky considering what I have just said and I cannot reply to it once and for all. However, I am particularly interested in biennales that involve local communities or at least try to consider or target them. In that respect, I heard that the main success of the new Cochin Biennale in India was the attendance of the local population, who was massively queuing to see the show. I think it is something we should carefully look at and interrogate ourselves on.

In contrast, the afflux of professionals during the opening week of the Venice Biennale is sometimes seen as an invasion. Hotels are assaulted and vaporettos are so full that additional shifts are organized.

Although the Venice biennale is definitely commercially profitable, one might wonder about the cultural value the inhabitants of the island get out of it. On the same line, a few years ago I attended a new biennale in a country where English is almost not spoken. However, wall texts and all the explanatory boards were in English.

This fact leads to the following question: who are biennales for?

During the last editions of the Biennale, there have emerged many events officially aimed at investigating the "Arabian culture". Not only we have seen the birth of national pavilions, such as the Emirates'- but there was also a great feedback among the collateral events, with exhibitions such as "The Future of a Promise" (Edge of Arabia, 2011). Do you think the adjective "Arab" is effective in representing a common cultural base? How would you judge, partially or overall, such initiatives?

Bérénice Saliou: The adjective “Arab” is a very vague notion. Morocco and the Emirates have little in common for example. Even though Islam is the dominant religion in both countries, people do not speak the same language, their history and their socio-political situations dramatically differ and they are more than 3500km away from each other.

The contemporary art world seems to be constantly in need of putting artists in boxes. There used to be schools and movements. Now, there are geographical areas (look at the curatorial approach of the Saatchi Gallery this past few years).

But what does the adjective “Arab” mean here? Is there an Arab art? Let me just rephrase the question through taking another example: what does “American art” or “American artist” mean? What are the similarities between a Columbian artist and an artist from Los-Angeles?

To go further, we can consider the term MENASA, often used in the contemporary art world to designate artists coming from the Middle East, North Africa or South Asia. Even though it is sometimes tempting and practical to use such adjectives, we should think twice before doing so because it sometimes drifts from a European centered perspective.

Now, I don’t see how I could judge negatively the presence of the Emirates at the Venice Biennale because I was extremely happy with their curatorial choice. Mohamed Kazem is an important artist, not only for his work but also for his significant input in terms of education and transmission in the UAE. The immersive installation he showed at the biennale had previously remained as a project for more than 10 years, because of a lack of funding. It is an efficient and coherent piece and, to me, this matters more than anything.

Letting aside the exposition itself, do you find that the Biennale is offering concrete occasions for networking? What is the added value of being around during the opening days, for someone of the sector?

Bérénice Saliou: The most important biennales such as Venice, Sharjah or Istanbul do provide concrete occasions for networking but in quite a paradoxical way. Art professionals from all over the world gather in the same place, at the same moment.

Thus, you can be sure to make new encounters and establish interesting connexions. However, everyone is so busy and there is so much to see in such a short time that it is almost impossible to meet properly and work. In a cynical way, opening days of biennales are a way to affirm: “Hey look at me! I am here, at the right place at the right moment. I am a player in the game!”

Could you tell us about a work of art or a project that you have found of particular interest during this Biennale of Venice?

Bérénice Saliou: This year, the Golden Lion was attributed to Angola. It was a great surprise for everyone, even for the curators and the artist! They had not anticipated their nomination and, about thirty minutes after the announcement, around sixty hysterical journalists and art professionals were jostling in front of the closed door of Palazzo Cini.

The work by artist Edson Chagas consisted in stacks of colorful posters (originally photographs) showing details of architectures and abandoned items in the streets of Luanda.

The whole point of the installation was the dialogue that this fragile and simple work was establishing with the Renaissance masterpieces by Piero della Francesca, or Filippo Lippi. However, when the doors opened, the arty crowd rushed in the unlighted rooms and started to literally dismantle the piece without a gaze at the surroundings. What happened there that day is quite representative of the Venice Opening Days’ madness...

Interview with

Yasmina Reggad

Bérénice Saliouis a french independent curator living in Marseilles. She holds an MFA in Curating from Goldsmiths College in London and is Director of Trankat : an artistic residency and exhibition space she co-founded with artist Younes Rahmoun. Trankat is located in a traditional house within Tetouan’s medina (Morocco), listed as Unesco world heritage.

Saliou has curated projects and exhibitions including "No Signal Found" by Younes Baba Ali, (Galerie Arte Contemporanea, Brussels, 2011) et "Duty Free" by Katia Kameli (Vidéochroniques, Marseilles, 2012). She was selected as curator in residence for AIR Dubai 2013, organised by Delfina Foundation, Art Dubai, Dubai Culture and Tashkeel Galerie. She regularely writes for numerous magazines, galleries and artists such as Diptyk (Morocco) and Universes in Universe (Germany). She is a member of the Marrakech Biennale’s board.

Francesco Urbano Ragazzi is a curatorial duo founded in 2005. Invited to the Cité Internationale des Arts by the Mairie de Paris in 2008, FUR subsequently started to curate residency formats: Spot – studio dal vivo, promoted by the City Council of Venice (2010); Mirroring, funded by the Emirates Foundation (2011); Prima Visione, for the National Gallery of Cosenza (2013). During the same period, they were also included in the curatorial team of Art Enclosures, residencies for African artists instituted by the Fondazione di Venezia. Always based on a workshop practice, there are some recent expository projects such as the Internet Pavilion of Miltos Manetas for the Venice Biennale (2011 and 2013), Io Tu Lui Lei at the Bevilacqua La Masa Foundation (2012), L' Ile Flottante, as a section of the fourth Sinopale (Sinop Biennale, 2012).

Francesco Urbano Ragazzi lectured in accademic and public spaces. Among them: Università Iuav and Ca' Foscari (Venice), Zurcher Hochschule der Kunste (Zurich), Macro (Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome), Palazzo Grassi' Teatrino (Venice). They also collaborated with other institutions and events such as the Swiss Institute of Rome, National Ministry for Equal Opportunities (Italy), Fondazione March (Padua), Nuova Icona (Venice), Venice Agendas – Panel Discussions in and around the Biennale, Fondazione Giorgio Cini onlus (Venice), Les Rencontres (Paris), Alliance Française - Ile de France (Paris), European Cultural Association (Istanbul).

www.e-ven.net