Abraham Cruzvillegas

dal 4/5/2009 al 29/5/2009

Segnalato da

4/5/2009

Abraham Cruzvillegas

CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco

The Exhibition Formerly Known as Passengers: 2.9. For this show, the artist Abraham Cruzvillegas has created a video installation showing recent interviews of his parents. Conducted separately, the interviews give each parent's perspective on the story of how the family house was built in an undeveloped neighborhood in Mexico City. The artist will bring both his parents to San Francisco in order to watch the video for the first time and hear each other's story.

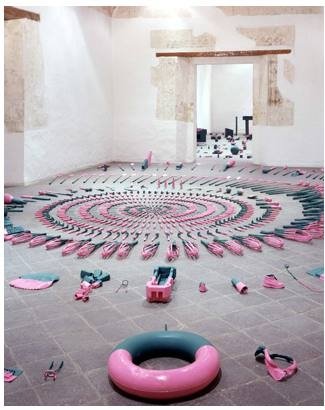

The Mexican artist Abraham Cruzvillegas is best known for his sculptures that transform everyday objects, such as found scrap wood and weathered buoys, into elegant compositions. Updating Duchamp's readymade technique while reflecting the specific locale of where the materials were sourced, his work highlights specific socio-economic circumstances around production. The artist plays the role of a scavenger, finding value in the discarded. He engages in an endless transformation process of materials, so that the mass production of buoys or glass bottles, for instance, is only the first step of the ongoing reinvention process in the life of an object. While Cruzvillegas's sculptures address issues of labor and credit, they also convey the purely formalist concerns of balance, structure, and the energy of an object. Exploring notions of instability, his delicate configurations communicate the fragility of an object's structural and seductive qualities. Autoconstrucción: Spatial Development Perspective (2008) is a graceful arrangement of found materials in which the objects appear to be held together of their own will. While preserving the original identity of each separate component, the objects are transformed into a composition with its own character, as though the sculpture has created itself.

Autoconstrucción: A Dialogue Among Angeles Fuentes and Rogelio Cruzvillegas

For this exhibition, the artist Abraham Cruzvillegas has created a video installation showing recent interviews of his parents. Conducted separately, the interviews give each parent's perspective on the story of how the family house was built in an undeveloped neighborhood in Mexico City. Cruzvillegas will bring both his parents to San Francisco in order to watch the video for the first time and hear each other's story.

Mamá: Sometimes I don't know who I am, myself… but ok, I'm María de los Ángeles Fuentes Vera, I was born here in the Federal District, downtown Mexico City. I grew up in Tacubaya and have lived here in the Pedregales of Ajusco, in this house, 41 years ago now, when I married Rogelio Cruzvillegas Villegas.

Some people of the city of Mexico use to say that beyond Tlalpan, San Ángel, Coyoacán, these dried up rocky lands that are part of Coyoacán municipality, were called "bad lands" because here there were only snakes, and more snakes. Many years ago these rocky lands begun to be inhabited to form the neighborhoods of Ajusco, Santo Domingo, Ruiz Cortines and part of Santa Úrsula.

The first time I came here was in December 1966, I came to the wedding of one of the sons of aunt Tachi whose name was Juan Prado Paleo, aka "Chespirito" because he's like that: tiny little runt. He married Delia Alcántar Vázquez. That December Rogelio and I had six months of knowing each other.

I always thought that beyond Pacífico and División del Norte avenues there were no more neighborhoods. This neighborhood for me was unknown and I was shocked because there were very few houses, these were half built constructions made with cardboard sheets, some with plenty of construction material, but all like that, somewhat bleak. Nevertheless, the wedding party was very good, there was churipo and mole and plenty of Uruapan "Rillitos" brand snake bite that was really good.

After the party that was nearby, in the street of Ixtlixóchitl, right around where we are, Rogelio told me: "Hey, check this out, I want to invite you to where I'm building, in a lot that is right around the corner, let's go," and I came with him. And the house, well it was really just a big room, a space there with an enormous ditch and then this little bathroom and that's about it. There were no fences, none of this construction where we are right now. This enormous room was divided afterwards into a bedroom, a little hall and a kitchen; and its roof was made of iron planks, which were stronger than the ones used in other constructions nearby that were made of cardboard

The first time I went out with him he invited me to a harpsichord concert performed by Luisa Durón, in the atrium of the cloister of El Carmen in San Ángel. That was in July of 1966, afterwards we got married in January of 1967 and sometime later we got married by the church and I came to live with him. Truth be told there was nothing here: there was a bathroom but no water, there were lots of books in that big room, an accordion, a cello, and a violin, there were windows, but no window panes

With the goal of forming a family, having kids, of reaching certain stability, to have something of our own, right? I mean owning something because I always paid rent in tenements in Tacubaya; and the idea of having a space of one's own where to live, even if it was within this scarcity, allowed us to imagine a future with something under our arms. Painfully aware of having almost nothing, but at the same time knowing you have something: a space where to live. That thought was what always drove me, when thinking about my sons and daughter, who were born and raised here. As a matter of fact, my son Abraham Francisco was born two blocks from here at the house of a self taught midwife, Doña Chelito González, likewise my daughter Eréndira, they're truly pedregalenses; Jesús, my youngest, he was born in a hospital.

…

This neighborhood, besides being popular and harsh, is one of struggle and fight; the people here have organized themselves self sufficiently in such a way as to stop much abuse. When officially recognized by a government institution, called Fideurbe, we were asked to pay a very high cost for every square meter and it caused us all a degree of discomfort, ill being and stupor. But all that led us to organize ourselves and within this organization of men and women, we managed to reduce the cost of land to 55 pesos the square meter. If you have 250 square meters, like this house does, it's not that much money, but it was a quantity which we couldn't pay at the time. And although we were given differed installment plans of three, six and nine months, many people even under such conditions could not pay. This caused much anguish and distress in the inhabitants of the neighborhood.

Once we got water and sewage services, we started to fight for schools because these parts were not officially recognized before the federal government, which at the time was called Departamento del Distrito Federal. For instance, my sons and daughter Rogelio, Francisco and Eréndira weren't able to go to school here because there wasn't any school to go to… So we had to take them all the way to Miguel Ángel de Quevedo and División del Norte, to a neighborhood called Atlántida, and often times there was no public transportation to get there and I used to take them and bring them back walking all the way from there.

Papa:Little by little the neighborhood started being formed as such, and streets appeared. Before that there was an emptiness all around, not one house, and suddenly, in front of our place, Doña Mimí's relatives from Puebla started building. And then the streets started to be drawn and one or two construction workers showed up, and so the construction began. Also, the people who came to sell building material took to telling others about this neighborhood: "They're selling lots, they're giving them away, they're invading the lots". So then, between 1967 and 1968, a big invasion took place.

Afterwards Santo Domingo was founded, it's an adjacent neighborhood, and at the time the historians and journalists used to say that it was "the wound of Latin America"… there were thousands and thousands of inhabitants.

People started coming from different places. And all of the sudden a church was founded and then the health center; afterwards it was very slow moving, very sad, very painful, because everybody believed that it was a neighborhood of thugs and criminals. Since it was abandoned, since there were no police, and then the mounted police arrived, but by then it was worse because the gangs of teenage hoodlums in Santo Domingo set a patrol car on fire and that became a media landslide. Anyway people kept on coming because finally this neighborhood was always very peaceful in social terms, which developed slowly.

…

So then, the rural atmosphere of when I first came here went through a transformation, just as the house lived one too. We made a small construction with a kitchen, two bedrooms and a small garden in the entrance. In those days, some construction worker friends I had asked me to teach them how to play the accordion, so in the afternoon we had us a little school of Norteño music and people would come to listen to us.

…

From 1964 and up to the 1980's, the neighborhood grew and it was easier to find work here. There was an increase in construction so for the most part it was construction workers that came. There was always work here for them.

…

Because it was easy to find work there was a flow of people, not only from my town, but from Arantepacua, Turícuaro, Comachuén, from Rancho del Padre, from Rancho del Pino, from La Mojonera, and San Isidro…Carpenters also came because people, instead of having their doors made out of metal, they still rather have them made out of wood. Afterwards, there were a lot of shoemaker shops, people being poor would have their shoes repaired instead of buying new ones.

…

Around where I live many have died… Lalita died, the Lord of the Faucet died, Don Manuel died, Doña Conchita died, Doña Mimí's mother died, and Doña Mica is very ill. So just like there was an invasion of people, people are also disappearing very fast, that is to say: I'm getting old.

And now it's packed, and I mean packed: saturated with peseros wherever you might want to go in the DF. Some of these cars go all the way to Tlalnepantla, and this is outside of the city, very far. When I started teaching at the University, there was a bus that would depart from Santo Domingo and take you to the University; imagine! You had to go all across Mexico City. Now there is an over abundance of cars, taxis, bus lines and needless to say peseros… It's a vice, the peseros everywhere, I think there are peseros that take you all the way down to hell! One never knows, honestly, I don't know the whole of this city, it's immense. One does not know where to walk or not to walk. To make a long story short: I don't even know the whole of this neighborhood.

Press Contacts

Brenda Tucker tel 415.703.9548, mail btucker@cca.edu

Kim Lessard tel 415.703.9547, mail klessard@cca.edu

CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts

1111 Eighth Street - San Francisco

Gallery Hours

Tues. & Thurs. 11 a.m.–7 p.m.

Wed., Fri. & Sat. 11 a.m.–6 p.m.

Closed Sun. & Mon.